Category: Defence

UK Paras Join Jordan’s Special Forces On The Exercise Designed To Make Enemies Notice. (Forces News)

General thoughts about the 2023 War against Israel by Hamas and the possibility of a political solution.

As well as being a military historian I have written about defence and security; advised journalists, authors, discussed the subject on television and radio and the following is my take on the current geopolitical situation.

At the time of writing (10 October 2023) Hamas terrorists have entered Israel and killed around 1,000 Israeli citizens and it is thought the numbers will increase. There are graphic accounts of babies, toddlers, entire families being massacred; it has also been claimed the Israel Defence force (IDF) found forty babies with their heads cut-off, others with their throats cut, and people burnt alive. The IDF recently announced that around 130 men, women and young children have been taken to the Gaza Strip who Hamas has threatened to execute. There is also evidence of women being beaten and raped sometimes Infront of their families.

In June 1967 war broke out between Israel and a coalition of Arab nations consisting of Egypt, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Lebanon, and Pakistan who were defeated by Israel within six days and consequently became known as the Six Day War. In 1973 there was the Yom Kippur War against Israel by Egypt, Syria and expeditionary forces consisting of Saudi Arabia, Algeria, Jordan, Iraq, Libya, Kuwait, Tunisia, Morocco, Cuba, and North Korea. Although often volatile and politically complex there continues to be no open hostility from these countries towards Israel.

A period of international terrorism

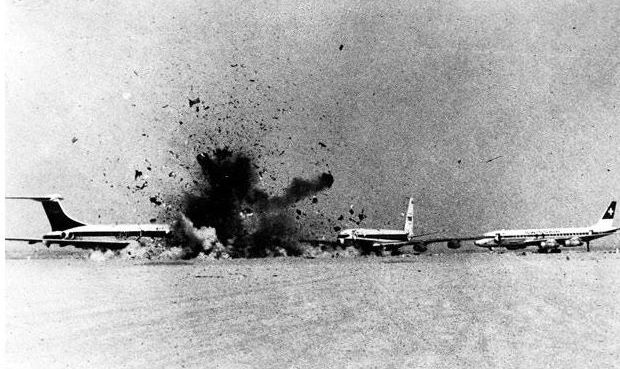

Dawson Field Hijackings by the PLO. Four airliners bound for New York and one for London were forced to land at Dawson’s Field, Jordan and blown up.

PLO hijacker Leila Khaled

After military action failed to destroy Israel the conflict was spread to Europe by international terrorists such as the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine General Command who attacked overseas Israeli targets and hijacked western airliners, but this increased support for Israel from western nations and attacks are now seldom outside Israel. There continues to be emotional language such as occupation and apartheid going back to 1948 but conventional war and the many terrorist attacks against Israel are seldom mentioned by people of protest who often overlook modern geopolitics as the driving force of continued violence.

Hamas. Their original manifesto was antisemitism blaming Jews for all wars supported by Jewish international bankers. This was later removed but continued to call for the destruction of Israel.

Hamas dominate the political life of Palestinian and is widely believed Iran has been providing finance, weapons, and training for Hamas terrorist since they took over the Gaza Strip and like the so-called rejection front Iran and Hamas share the same moto ‘Death to Israel’. According to the Wall Street Journal (8 October 2023) Iran help plot the attack on Israel over sever weeks and the Iranian Islamic Revolutionary Guard gave the final go-ahead.

It is inevitable the massacre of 1,000 Israeli citizens mainly in their homes and the brutal nature of their deaths will lead to a disproportionate military response against the densely populated Gaza Strip resulting in mass casualties among the civilian population. It may also be argued Iran and Hamas have used Palestinian civilians as pawns in an attempt to destabilise the region, further escalate the conflict and damage forthcoming talks and possible closer political relations between Saudi Arabia and Israel which would be a game changer in the middle east. Most Palestinians are not responsible for the massacres of Israeli men, women, and children but will pay the price because there is no such thing as a none military target in Gaza where weapons are hidden in mosques and residential buildings.

Many protesters continue to express anger over what they call Israeli occupation and expansionism but for Israel controlling Gaza is regarded essential for protecting their country. It is clear from current and ongoing events a One-state solution sometimes called a bi-national state is impossible until the people of Palestine have a stable political system that firmly rejects the Iranian proxy war supported by Hamas and Hezbollah. The massacres of Israeli citizens, the taking of hostages and hate speeches from Iran suggest many more generations of Palestinians will be used as pawns by state and non-state players, consequently, the barrier to peace is not connected with 1948 and many of the events that followed, a political solution leading to lasting peace is impossible under the current geopolitical landscape.

I forgot I gave the following interview on the Russian war with Ukraine.

Veterans Lottery: An Amazing woman and soldier.

In the News: My interview with Ankara Centre for Crisis and Policy Studies published 13 October 2022

Why do we continue to lose the Information War against Daesh and al-Qaeda Affiliates? (First published 3 March 2016)

“Understanding and harnessing the persuasive powers of narratives is central to US and international counter-terrorism efforts. There is an urgent need to understand the narrative tactics of terrorist recruitment and equal if not greater need to destabilize the weakness of those narratives.” (Ajit Maan PhD, Narrative Strategies: Counter Terrorism http://www.ajitkaurmaan.com/books-and-articles.html)

Since 9/11 we have seen increasing sophistication in the use of narratives by al- Qaeda, its affiliates, and especially by Daesh, to shape the minds of their international audience. Well scripted secular narratives often illustrated by skilfully edited visual images drive home the message to young people that they are being oppressed by the western world- the west is inherently racist and all their experiences: lack of work and education opportunities, marginalization and all social problems, both real and imagined, are because of the corrupt western governments which is being supported by Christian-Jewish elitism.

Secular narratives are designed to create a culture of blame towards the western nations and those outside their peer group. Religious narratives, or to be more precise the extremist’s version of Islam, provide not only strong moral justification for violent Jihad but also provides a peer-group of like-minded individuals willing to use violence to address their perceived grievances. The occasional outbursts of resentment from an individual has been transformed into collective action to violently challenge the status quo.

Once an individual has been suitably spoon fed with the urgent need to act, violent Jihad is far easier to sell as a religious duty. The cognitive effects of the combination of secular and religious narratives closely fit Jerome Bruner’s (American psychologist) concept of ‘Narrative Construction of Reality.’ It may also be described as ‘Narrative Based Knowledge’ (Nicolas Szilas).

Although narrative analysis (narratology) can be complex, in principle we can break it down into Emotions, Motivation and the mobilization of Action.

An example of Daesh attempting to increase civil unrest in the USA and promoting the illusion of the Islamic State embracing equality among all races.

Narratology (the analysis of narratives in their many forms)

Since the 1960’s Narrative theorists have always shown interest in the relation between minds and narratives, or to put it another way, the cognitive effects of narratives. Although many argue that Narratology was starting to be regarded as an important area of research during the 1960s, throughout the 1960s and well into the 1990’s this research was being conducted by scholars from a wide variety of disciples which included: Social Anthropologists, Philosophers, Social Historians, Psychologists and Sociologists. Each disciplined tended to work in isolation resulting in their findings, the development of concepts and analytical tools not being shared with other disciplines and there were no peer-group reviews from outside their profession. I am pleased to see that Narrative Strategies (http://www.narrative-strategies.com/) has started to address this major shortcoming by establishing an increasingly influential public platform consisting of a coalition of scholars and military professionals involved in the non-kinetic aspects of counter-terrorism, irregular warfare, and social conflict.

When attempting to analyse narratives from Daesh and AQ affiliates we find ourselves attempting to identify how these various narratives are designed in order to “construct reality” for a specific audience. Only then is it possible to construct a workable counter narrative. Furthermore, an added difficulty is due to the fluidity of the narratives used by Daesh and AQ. These organisations closely monitor all government communications, the media and pay close attention to international affairs and western military initiatives. They look for every opportunity to distort the original message to fit their propaganda objectives.

A simple example which has been much quoted occurred shortly after 9/11 when George W. Bush said, “this crusade, this war on terrorism is going to take a while…” within hours the word ‘Crusade’ was used to project the image of America being the aggressor against Islam. They received a further propaganda opportunity after columnist Alexander Cockburn, suggested in the Counter Punch magazine, that Bush was referring to the “Tenth Crusade” in which he numbered America’s War on Terrorism to follow the nine medieval crusades between 1095 and 1272. As Bush used the word ‘crusade’ and an American publication ‘confirmed’ the USA was going to continue the medieval European crusade against Islam this was not only used as confirmation that America was bent on destroying Islam, 9/11 was also portrayed as being ordained by God! As can be seen by this example of one word resulting in a huge propaganda victory which was used for moral justification for terrorism, recruitment and proof that Jihad against America and its western allies was the duty of all Muslims, most government communications which lack close scrutiny may be used for propaganda purposes simply through careful manipulation based on cultural and social interpretations; and the distortion of the original message to support the extremist mythology based on their view of an unjust and un-Godly world in which the west continues to be responsible.

The current threat from international terrorism cannot be addressed by conventional and SOF alone and the use of soft power, for example, the ability to shape the preferences of others through appeal and attraction, are essential for countering this new terrorist phenomenon based on ideology and destruction.

I agree with Paul Cobaugh who says, “The US soft power tool box is half empty and poorly stocked… we are employing an ineffective, ambiguous, antiquated strategy and there is a limited number of true, trained craftsmen…”

(Paul Cobaugh, Soft Power on Hard Problems (forthcoming) ed. Ajit Maan, Ph.D. and Brig. (retired) Amar Cheema.)

I would add, this is not just a US problem, all western nations share the problems addressed by Paul Cobaugh. Again, I also agree with Paul Cobaugh’s assertion that “Daesh is a media influence effort supported by arms and brutality rather than the other way around” and “We require sophisticated media campaigns in the media and on the ground…”

Due to the powerful and fluid nature of the plethora of Daesh narratives I also agree with Paul Cobaugh’s view that those responsible for government or military communications must be capable of thinking out of the box and we must also utilize the media, diplomacy, business development etc. This multi-faceted approach which Paul Cobaugh discusses in great detail, are clearly essential for establishing workable and fluid counter narratives both inside theatres of operations and also to address secular and religious narratives which continue to be powerful recruiting tools especially when it comes to valuable men and women living in the west and also provides opportunities for the development of the ‘self-radicalized’ and so-called lone wolf attacks.

Furthermore, any efforts in the form of refugee aid and stability development, irrespective of whether this is a government or NGO initiative should be widely promoted. (See Ian Bradbury, Narrative Strategies http://www.narrative-strategies.com/) Humanitarian work of this nature helps counter the narratives depicting western nations being led by the epitome of evil (the United States) and the Christian- Jewish alliance to crush Islam.

The Digital Culture: Finding and analysing the continuous flow of Narratives.

Apart from analysing narratives with the intention of countering their message or story, such analysis may also provide information on the target audience, the writer and his/her intentions and this is especially true with western audiences. Of particular interest is language syntax- informal speech patterns, country or regional variations, jargon, teen idioms and expressions, Pidgin English etc. However, an increasing problem is finding the narratives to analyse in the first place.

It is well known that Twitter, Facebook and YouTube continue to be used by Daesh and AQ affiliates for the dissemination of propaganda and are also used for recruitment. It is also known that as soon as these accounts come to the attention of network monitors they are deleted but only to be replaced by large numbers of new accounts which are often linked to disposable email accounts. Furthermore, some accounts may deliberately use expressions which are not connected with extremism or religion in order to avoid detection and subsequent suspension of the account.

In 2013 I said, in ‘Narrative: Pathways to Domestic Radicalization and Martyrdom’, every effort is being made to recruit technical-jihadists and IT professionals specializing in security should not be complacent by believing they are the smartest people in their field. Some of my IT contacts remained adamant: they held graduate and post graduate degrees and had far greater knowledge and experience than any terrorists. Since then we have seen an increasing degree of cyber sophistication and media manipulation from Daesh technical jihadists.

Although Daesh continue to use multiple Twitter, You Tube and Facebook accounts and easily form new accounts to replace those which have been removed, these and other mainstream social media networks are now mainly used as conduits to steer willing audiences and potential recruits to more secure networks which us various forms of encryption and the choice of network is sometimes used to target a particular geographical area.

Blackberry Channel

Blackberry’s media platform, ‘Channel’, according to IBRANO, have over 1 million channels which can only be accessed through Blackberry Messenger and users can start channels covering topics of their choice. The Al-Hayat media wing of Daesh, who publish the Dabiq Magazine, have been found using the Blackberry Channels. According to ARS Technica, Channel is used to target an English speaking audience and is regarded as a versatile recruiting tool which Daesh regards as far more effective and more secure than their estimated 46,000 Twitter accounts (ARS Technica).

In 2015, the BBC reported that “new platforms are popping up on a weekly basis in order to get away from mainstream social media platforms and to hide in corners…” (BBC Trending, 13 March 2015)

We now find that many of the narratives we need to address along with the planning of attacks, recruitment information, bomb making instructions; ideological literature, advise on how to engage in so-called lone wolf attacks against soft targets, and other instructional, motivational material and advice, is being sent to willing audiences and the fully radicalized via secure mobile messaging apps some of which have been designed by technical jihadists.

Telegram, which is described as a cloud-based instant messaging service for both mobile (Android, iOS, Windows Phone, Ubuntu Touch) and desktop systems (Windows, OS X, Linux) allow users to send messages and exchange photos, videos and files of any format up to 1.5 GB in size and has extensively been used by Daesh and AQ Yemen (AQAP). This was a natural choice simply because Telegram provides optional end-to-end encrypted messaging with self-destruct timers. According to promotional material it is “Pure instant messaging — simple, fast, secure and synced across all your devices and has over 100 million active users.”

For Daesh, Telegram provides two major security requirements. Firstly, it has been widely said Telegram does not disclose where it rents offices or which legal entities it uses to rent them, citing the need to shelter the team from unnecessary influence and protect users from governmental data requests. Secondly, it is also widely claimed that once the self-destruct timers have been activated and all data has been deleted no data can be recovered using forensic software. Naturally, both claims are open to debate.

Telegram and other encrypted apps are also used to distribute their publication ‘Inspire’ which concentrates on training and their glossy magazine Dabiq which has a strong media brand and is designed for the dissemination of ideological congruent propaganda to promote radicalization among sympathizers and foreign fighters mainly from the English speaking nations.

Daesh also maintain their electronic presence and distribute their narratives by adopting per-to-peer technology. For instance, anonymous peer-to-peer networks such as Ask.Fm was used for one-to-one interaction, and the distribution of information on how to join Daesh.

It is also known that Firechat app has been utilized for covert planning of coordinated attacks and also for international recruitment.

According to the Office of University Programs and Technology Directorate, US Department of Homeland Security, in December 2014, “After profiling this group’s {Daesh} use of cyber technology for over a year they found the use of a variety of technical platforms, diverse languages and tailored messages… cyber technologies also facilitate internal co-ordination (e.g. Command and control) and focused information flow externally with the broader Umma {the whole community of Muslims bound together by ties of religion} and potential foreign fighters.”

This paper also explains Daesh has a sophisticated understanding of cyber marketing, organisational branding and has robust and a fluid recruitment arm and highlights the kind of personal information they can access.

Apart from the intelligence and security implications associated with encrypted communications over several platforms it also presents a series of hurdles we must overcome before we can counter the stream of narratives from Daesh and the various AQ affiliates.

Daesh using race to promote the ‘virtue’ of their ideology.

The Virtual Caliphate: Daesh and Their Use of Social Media (First published 2 May 2016)

The Islamic State, widely known by opponents as Daesh, has proved itself to be an innovative organisation skilfully using technology and inventive methods to manipulate users of social media and compelling global news networks to run their stories. The methods they employ to radicalize without physical contact and the relationship between individual radicalization and the consumption of extremist material which, by its very nature involves a complex mix of variables, continues to evolve. Consequently, a detailed examination of the Virtual Caliphate is beyond the scope of this paper and the following is intended as a brief introduction to the subject.

According to Hemelin, attitudes are part of the brain’s associated networks; people interact with the environment based on how they perceive and interpret it. This is, people form an internal (cognitive) map of their external (social) environment and these perceptions rather than objective external reality determine their behaviour. Persuasive media messages, in this case social media, are built on the premise that behaviour follows attitude, and attitude can be influenced by the right message delivered in the right way. (Trigger Factors of Terrorism: Social Marketing as a Tool for Security Studies, Nicolas Hemelin, Al-Akbawayn University, Morocco)

Likewise, world events and social issues, both real and imagined, are beacons by which a person forms a cognitive map of one’s environment from which an interpretation of reality is formed. Furthermore, in the case of extremist narratives of hate and retribution, these do not act in a vacuum, they must be accompanied by supporting ideas to reinforce the belief so the target audience becomes detached from reality.

The technically astute and media savvy Islamic State’s (Daesh), official messages on social media are supported by several thousand sympathizers and followers, called ‘fan boys’, who regularly re-circulate official content from Daesh propagandists. In the case of Twitter, to greatly increase the coverage of their extremist messages a hashtag campaign was organised. This simply entailed hijacking popular hashtags such as those related to major sporting events to promote links to extremist websites where anyone can anonymously post messages and upload images. Daesh also created their own app, ‘Dawn of Glad Tidings’ to efficiently tweet messages to followers.

Although the accounts of extremist organisations continued to be closed and their material removed from social media platforms, this group, like other extremist movements, remain flexible and resilient. After an account has been closed other accounts are created and quickly publicized via various links and websites. ISIS also maintains a large number of backup accounts and continues to identify more social media platforms to increase their digital presence.

An estimated 10 million people live in Daesh occupied territories (BBC Islamic Group Crisis and maps, 27 April 2016) which is a closed world with no journalists or independent observers. The only source of information for the world’s media originates from the Daesh media center called Hayat which has offices throughout the occupied areas and is controlled by the Media Council. Different areas of propaganda are managed by different departments within the Council and before being released all communications are structured to meet a variety of requirements. This includes ensuring the global media use their content so their messages and visual images gain access to millions of homes. Official communications from Daesh is greatly supplemented by unofficial material uploaded to social media and websites by their supporters.

The glossy and professionally produced Dabiq magazine, which is translated in English, French and German and is available via the Internet, is thought to be written by professional journalists in occupied areas who were given the option of either working for Daesh or be killed.

The virtual world

Daesh and other VE narratives found on social media and various websites cover a number of separate themes which may be woven together in order to appeal to a certain audience or to encourage an appropriate emotional development. This is essential for the successful engagement and radicalization in virtual space which differs from real-world face-to-face radicalization. According to Von Behr, whose research is based on the conviction of 15 extremists, “the Internet affords more prospect for radicalization… {the internet} was a key source of information, communications and propaganda for their extremist beliefs… {it} also provided greater opportunity than offline interaction to confirm existing beliefs…”

Research conducted by et Al, in 2014, found that after sampling 199 lone actor terrorists, 35 percent of the sample virtually interacted with a wider network of activists and 46 percent learned aspects of their attack methods through virtual sources. They also found that 65 percent of al-Qaeda inspired actors were significantly more likely to learn through virtual sources.

Forms of virtual interaction include: reinforcing prior beliefs, seeking legitimacy for future actions, disseminating propaganda and providing material support for others, attack signalling, and attempts to recruit others (Gill and Conway,2015). Forms of virtual learning include, ideological content, opting for violence, choosing a target, preparing an attack and overcoming hurdles.

It is also evident that Daesh and other terrorist movements use the Internet to create a ‘brand image’ to assist them in marketing their ideology, recruitment and influencing media coverage.

There is also what Gill and Corner call, ‘Current Problem Factors,’ “World events and newspapers provide the heads-up about the dangers of the world and opportunities related to one’s degree of concern towards world events…” and these concerns are exploited through the use of appropriate narratives. (What are the Roles of Internet Terrorism? -Measuring online behaviors of convicted UK Terrorists, Paul Gill, University College London, Maura Conway Dublin City University, 2015)

The full spectrum of narratives produced by Daesh is large: some are interrelated and link various secular and religious beliefs, whilst others provide ‘evidence’ supporting the extremist’s views.

Common themes include: sociological and political, agitation and integration, extreme violence, mercy, victim and blame, war/Jihad; utopia democracy and apocalyptic.

Sociological and political narratives

Sociological narratives, which are often used in tandem with political narratives, may include poetry, visual images and ‘personal’ stories to help maintain the illusion of Daesh’s self-styled caliphate being a democratic utopia. Whilst the political narratives may be paired with tactical and strategic narratives promoting emigration to the Caliphate; attempts to sell the belief of being the duty of all Muslims to support the Caliphate and the need for the birth of children for the Caliphate to grow, prosper and provide the next generation of jihadists known as ‘cubs. ‘

Strategic Narratives

Strategic narratives have long-term goals and seeks to establish and maintain the organisational line of ambiance (Quillian Foundation). The content may appear largely mundane and insignificant: stories and visual images of children playing in the streets, various social events, shrines being destroyed; western style clothes, make up and western consumer goods being burnt. As well as further enforcing the message of utopia, it is also designed to project the image of the ‘Islamic purity’ of the Caliphate and rejection of western values and culture.

Agitation and Integration Narratives

Agitation narratives are intended to encourage passive supporters to become active members of the organisation. Active membership includes the recruitment of foreign fighters or joining their support structure as technicians, logistics specialists, being responsible for organizing safe houses and documents etc. Integration narratives are designed to encourage loyalty to the system of beliefs promoted by Daesh. Again, Agitation and Integration narratives are often paired or work in tandem for optimum effect on the target audience.

Rational and Irrational Narratives

Rational and irrational narratives are frequently used to distort facts (disinformation) and are mainly used as persuasive tools to reinforce the message of the movement’s superiority and the image of a utopia which must be defended at all costs. Furthering the synthesis of lies, exaggerations and facts are essential for the survival and growth of Daesh and its caliphate. None of the various themes are discrete elements within the narrative strategy: sociological, political, rational and irrational narratives may be used separately or in combinations to spoon-feed their selected audience.

Extreme Violence

Extreme violence may be regarded as the vanguard element of the various narratives which encourages beliefs such as vengeance; supporting the self-proclaimed ‘Islamic’ superiority of Daesh and justifying revenge on behalf of all Sunni Muslims against the Christian-Jewish crusaders and other unbelievers. Within the long list of unbelievers, we also find Sunni Muslims who refuse to follow the organisation’s religious ideology and world views. As with all narratives and propaganda strategies the content and structure is often tailored for specific purposes.

In November 2014, the Daesh media centre produced a video that documented the execution of three members of the Syrian Army and this was intended for a different audience than the one in which Japanese journalist Kenji Gotto was killed. The video of the barbaric execution of Kenji Gotto contained the caption “A Message to the government of Japan”. We have also frequently seen executions of alleged spies as part of a terror tactic to discourage dissent from the population under Daesh control in Iraq and Syria.

The promotion of extreme violence is also used for the self-gratification of supporters; to intimidate enemies; and to provoke outrage from the global media to ensure further publicity opportunities.

Mercy Narratives

Mercy narratives often work in tandem with extreme violence and are connected with repentance to God and Daesh. An example often quoted is the April 2015 video entitled “From Darkness to Light”. Here we see captured combatants from the Free Syrian Army, Jabhat al-Nusra and the Syrian Army who were all former enemies of Daesh. The carefully orchestrated and professionally edited video shows them reneging their former ‘Islamic’ beliefs and swearing allegiance to Daesh. According to this propaganda video, Daesh is compassionate and will forgive their enemies if they follow the ‘true’ path of Islam and swear allegiance to Daesh and the Caliphate.

Victim Narrative

Victim narratives designed to encourage paranoia is a constant theme and a powerful recruiting tool. This promotes the belief of the global war to destroy Islam and this narrative and propaganda tools are often used alongside extreme violence. For example, Jordanian pilot, Mudh al-Kasabeth who was burnt alive shows the binary opposites of victim and extreme violence.

On 3 February 2015, Daesh produced the video “Healing of the believers Chest” the words ‘healing’ and ‘believer’ are positive words which suggest beneficial treatment! However, this is the title of the video documenting Mudh al-Kasabeth standing in a steel cage before being doused with petrol and burn alive. Shortly after the Jordanian pilot was engulfed in flames, footage of coalition airstrikes was faded in before showing dead children ‘allegedly’ killed during the airstrikes. This video was intended to reinforce the justification narrative, and to remind its audience of the legitimacy of retaliation and the duty of all Muslims to join jihad. The caption at the end of the video, “What is the ruling on burning Kafir until he dies, Office of Research of Fatwas, 20 January 2015,” was intended to provide religious justification for the murder.

Another example shows jihadists carrying dead children before showing a group of alleged ‘spies’ being burnt alive in a car and another groups of ‘spies’ being beheaded by explosive necklaces. These images were for the benefit of the global news networks who, as Daesh predicted, published still images across the world and the video was shared tens of thousands of times within two hours of being posted on social media. Images and descriptions of dead children remain a powerful driver for creating a victim mentality leading to paranoia and a desire for ‘divine’ retribution by becoming a ‘soldier of God’.

War Narratives

Such narratives are intended to create and sustain the illusion of power, military discipline, valour; and feeding the idea that Daesh has a ‘real’ army, which further adds to the illusion of a ‘real’ nation state or caliphate. War narratives are also a powerful tool for recruiting foreign fighters.

Utopian Democracy

The Utopian building narrative promotes social well-being, brotherhood, sisterhood; the multi-ethnic makeup of the caliphate which embraces all colors and nationalities without prejudice and their claim, “all are equal under the Islamic State”. Daesh propagandists and their supporters take every opportunity to promote the false image of an idyllic and harmonious life under their rule. We see a constant stream of emotive stories of happy families which reinforces the myth of equality and a common identity for all Muslims living in the Caliphate. 20-year-old Aqsa Mamood, (aka Umm Layth) who was slowly radicalized by reading extremist articles and posts online in her bedroom in the UK, is believed to have played a major role in recruiting many women from the west. As well as being a prolific blogger she also engaged in debates on Twitter and gave advice on how to join Daesh. British sisters, Zahra and Salma Halane, through social media became role models for others to join Daesh. These female groomers promoted the Utopian image of nice houses, friendship, good husbands and a shared common identity.

Through careful branding and a continuous marketing campaign the Caliphate which was created by Daesh and is said to have been ‘ordained by God’ is, for many of its supporters, inseparable from the Umma (world community consisting of all Muslims) and is the unique selling point on social media. As the majority of Daesh supporters have never visited the so-called caliphate and their only knowledge is based on the propaganda version or, to be more accurate, a ‘Cyber Caliphate’, and Daesh remains popular, this may be seen as further evidence of the persuading influence of their narratives which alter and reinforce beliefs and attitudes.

Apocalyptic Narratives

The apocalyptic narrative: the continued war between good and evil and those dedicated to jihad having God and the angles on their side, remains a powerful motive for joining the ranks of the jihadists and a willingness to die for the cause. This approach also allows extremists to add additional enemies against Islam as they see fit.

Whilst western governments continue to rely on military options to address Daesh and other violent extremists and neglect the urgent requirement to employ counter-narratives which work in conjunction with a variety of other soft power options, global jihad will continue to grow.

Further reading on narratives and soft power can be found on the Narrative Strategy blog which is the public platform of a coalition of scholars and military professionals involved in the non-kinetic aspects of counter-terrorism, irregular warfare, and social conflict. http://www.narrative-strategies.com/

Basic Analysis of Social Media: Examining the use of narrative-based drivers for remote radicalization. (First published 3 August 2016)

As I am fortunate to have a large number of data analysts and those involved in the behaviour sciences among my LinkedIn contacts, I would like to point out this paper is not intended to bring anything new to the study of radicalization or extremist behaviour. I also feel sure that many of my contacts in this field will put forward various other methods which may be used to collect the same datasets mentioned in this paper.

Several years ago, as part of my research into the induction and radicalization process used by AQ affiliates via social media (SM), I spent a considerable amount of time reading academic papers on SM mapping and human behaviour. This information allowed me to research SM, the web and dark web in order to increase my understanding of the drivers associated with violent extremism (VE) and the mindsets of vulnerable people who may be psychologically manipulated to join the extremist cause. It also allowed me to examine and test new theories put forward by various academics.

The following is a basic introduction to the subject which is based on the research of others and which I have modified for my own research needs. Furthermore, due to the limited scope of this paper I have not included data associated with demography, gender; or the analysis of text and visual images which are to be found in the ‘extremists’ virtual world of their making.

Finally, although I and other members of the Narrative Strategies Team (http://www.narrative-strategies.com/) have a comprehensive understanding of the narrative based drivers associated with VE, I have found the following allows us to examine these drivers working over time and space along with the behavioural changes experienced by some members of the target audience.

Analysing Social Media (SM networks)

Virtual social networks, like those found in the ‘real’ world, consist of relationships and relationship building blocks. An examination of this network reveals a combination of relationships which create identifiable patterns of connected people, groups and organisations. As explained later, this virtual social network which appears to allow users to remain anonymous provides a false sense of security where members are willing to express their concerns, frustrations and other personal information which they may not be willing to discuss in the real world. This provides an indication of an individual’s vulnerabilities which may leave them open to psychological manipulation. When one examines the communications between like mined individuals within this network it may first appear to resemble a peer-group support network which by its very nature encourages additional personal information to be shared with ‘like-minded’ people. Accordingly, extremist groomers and recruiters can select suitable individuals who may be radicalized.

Virtual Social Networks

It is easier to regard social networks as consisting of social entities: actors, distinct individuals, groups and organisations. We must also be prepared to follow these entities as they migrate to or simultaneously use other SM platforms. For instance, Twitter is limited to the maximum use of 140 characters (Tweets) and due to this limitation member who are of interests to extremists are often encourage to join a similar network on another SM platform with less restrictions and/or is considered more secure. Consequently, it is not uncommon to find the same social entities on various SM platforms.

Relationship ties (Contacts)

Some relationships which are tied to others across the network/s are said to be ‘informal’ because they are not widely known by others entities of the network under examination. For example, on LinkedIn we often find third degree contacts commenting on updates posted by members from outside their network simply because the commentator is connected to one or more of the writers’ first degree contacts. Such entities, in this example LinkedIn members, are often referred to as ‘Muktiplexity’ or ‘Multiplex’ because these individuals are actors with ties to other actors connected to you. I plan to cover this concept in greater detail at a later date during my examination of Russian trolls and the information war.

The Two Node Network consists of actors who may not have direct ties with each other but they attend similar events within a community (Mosques, sports clubs etc.) or may regularly visit similar websites. Although there are no virtual or physical connections, this provides an opportunity for prominent actors (Focal Actors) to form a false rapport with members of the Two Node Network and the opportunity to form a ‘weak’ link. The establishment of ‘strong’ links are only attempted after an individual is thought to be of interest to the extremist cause.

Egocentric, also called personal networks, tie directly with Focal actors (those with influence, I.e., groomers, recruiters, propagandists etc.) in the network. Hanson and Shneiderman describe this as, “Social Centric or complete network consisting of the relational ties among members of a single bounded community. (Social Network Analysis: Measuring, Mapping and Modelling Collections of Connections, D. Hanson and B Shneiderman, 2010).

The examination of networks also allows us to develop what some academics call ‘name generators’ which is simply the names of social entities, in this case people, who frequently communicate with the focal actors. Hanson and Shneiderman call those names generated by the focal actor, ‘the actors alters’.

The use of name generators, as advocated by Hanson and Shneidrman, allows for the identification of strong ties across a dense network. To identify weaker ties in more wide ranging networks, acquaintance name generators can be used.

Another useful tool discussed by Hanson and Shneiderman, is the Positioning Generator. This allows the researcher to identify people who fill a particular ‘valued’ role or position within the network and therefore have access to a range of resources. These resources may include professional knowledge, or work related experience beneficial to an extremist group.

Psychological Manipulation

Apart from the same narrative based drivers being used within the real and virtual world, we also find the same methods used to encourage members of their target audience to express their concerns, frustrations, aspirations and how they see themselves. This information is used to psychologically manipulate suitable members within the network and tie them to others with similar mindsets. The linking of suitable individuals within a network will often reinforce these concerns and produce suitable conditions for physiological manipulation. A United Nations report describes this as, psychological manipulation, “to undermine an individual’s belief in certain collective social values, or to propagate a sense of heightened anxiety, fear or panic within a population or subset of the population…” (The Use of the Internet for Terrorist Purposes: United Nations Office of Drug and Crime, NY 2012) It is also widely acknowledged that certain cognitive propensities can combine to create a mindset that presents a high risk of being radicalized (see Drivers of Violent Extremism: Hypotheses and Literature Review, RUSI, 16 October 2015) and it is these propensities which extremists seek to identify within members of the network.

Social media has made social connections and networks more visible and open to research. “The internet and its use by terrorist organisations, individual members, supporters and recruits afford new avenues for assessing information about groups and their activities…” (Lorraine Bowman-Grieve, Security Informatics, 2013, 2:9) As Bowman-Grieve says, “individual reasons why people become involved are many and varied, with no single catalyst event that explains involvement.” However, research indicates that involvement is a gradual process that occurs over time and the development of this process, which is driven by narratives and supported by inter-personal bonds that have been created for this purpose, can be examined through social network analysis.

By analysing network activities over a period of time not only do we see the use of narratives as efficient drivers towards extremism, we also see the development of identities being slowly formed. This includes perceived victimization and attempts to convince individuals they are victims and linking this to a common or shared identity and the legitimization of violence to address these perceived injustices. We also see the development of dualist thinking which supports the extremist’s’ view of the world, other cultures, religions and western society.

PDF version for downloading

Alan Malcher

The Kremlin False Narrative: the myth of fighting the Ukraine Nazi regime and its western supporters

The number of Russian soldiers killed in Ukraine are known to be high, but figures vary considerably and one of several unconfirmed reports recently claimed, “So far, around 18,000 have been killed and over 30,000 wounded” and many images of destroyed armour, convoys and dead Russian soldiers support many claims of high Russian losses, but whatever the true costs these continue to be kept from the Russian people.

Alleged war crimes now being investigated

The world continues to hear disturbing eye witness accounts supported by images of mass graves, civilians shot in the streets, mutilated bodies and other alleged war crimes committed by Russian troops which are currently being investigated by international prosecutors. At the time of writing Russia has been suspended from the United Nations Human Rights Council and in response to this decision Putin’s spokesman, Dmitry Peskpov, told journalists “Everything is blamed on Russia” and like the Kremlin he and other Putin supporters reject evidence to the contrary. The Kremlin also made the opaque statement, “they will defend their interests.” (BBC News 7 April 2022)

After the introduction of draconian laws, the independent press in Russia was purged and replaced by journalists and news networks loyal to the Kremlin and by design there is little access to non-Russian news services. According to recent reports from inside Russia Kremlin misinformation/disinformation continues to be a powerful tool for shaping Russian public opinion.

Some researchers claim western sanctions and the invasion of Ukraine, which the Kremlin call de-Nazification, has been be used to great effect by the Kremlin news services and 83% of Russians approve of Vladimir Putin’s ‘Special Operations’ and seven in ten Russians have negative feelings towards NATO, United Sates, European Union and others opposing Russian aggression.

The Kremlin’s success during their battle of perception continues to be based on narrative identity and the narrative of the nation by looking at the past to create motivation and justification for the present through constant reminders of the Soviet Union’s Great Patriotic War (WW2) against Nazi Germany and labelling Ukraine and its elected government as ‘Nazis’ can be seen as the most single most powerful element for unifying Russian national identity whilst using visual metaphors to deny everything including war crimes whilst blaming others.

According to various well placed commentators many Russians believe these war crimes are ‘false flags’ and part of a western conspiracy led by America and NATO during a continued proxy war against Russian and Dunbas was sold to America to allow their nuclear weapons to be aimed at Russia.

According to Alexandre Baeva, Coordinator of the ECHR Program on Human Rights, Putin setup a media channel to encourage ‘good citizens’ to report ‘traitors’ and Russia is like 1939, also according to Baeva “People are scared and informing on each other.”

Although Kremlin messaging appears to have resonated among normal Russian citizens indications suggest their information war is failing to influence a significant number of people living in western democratic countries and have increasingly began targeting Africa, south and southern Asia and this is supported by the number of trolls from these regions found on social media echoing Kremlin propaganda.

Pdf version for download