Due to conspiracy theories and published accounts which vary considerably the story of Suzanne Warenghem and her treacherous husband Harold Cole is complex and beyond the scope of this short article. Consequently, the following is an overview of events leading to the deaths of an unknown number of agents and French citizens of which Suzanne Warenghem, who later changed her surname to Warren, was unaware until her husband was exposed by other agents.

In an article written by Jacques Ghémard he describes Suzanne Warenghem as a 19-year-old British agent serving with the Special Operation Executive (SOE) who worked with the PAT escape line. If Warenghem, as Ghémard states, was serving with SOE she was likely to be a member of DF Section which was an independent subsection within SOE responsible for escape and evasion which worked closely with similar organisations including MI9, and this would account for her connection with the escape line.

After being arrested, which is discussed later, Warenghem was sent to Castres prison in southern France where she met Blanche Charlet an agent serving with SOE’s F Section who had been captured along with her wireless operator Brian Stonehouse. The two women quickly became friends and later escaped together during an audacious mass escape consisting of around 37 prisoners. Several decades after the war Blanch Charlet became relatively well known by historians but Suzanne Warenghem along with her war service and achievements as an agent was overshadowed by the story of her treacherous English husband Harold Cole.

After the war Airey Neave (MI9) said “Cole was among the most selfish and callous traitors who ever served the enemy in time of war”

James Langley who also served with MI9 said, “Cole was a con man, thief and utter shit who betrayed his country to the highest bidder for money”.

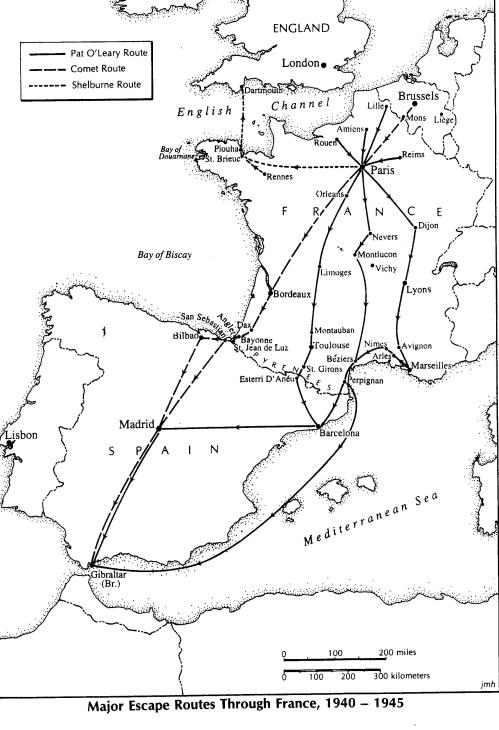

The PAT Escape Line

Susanne Wareneghem and her husband Harold Cole worked for the Pat O’Leary Line which was also referred to as the PAT Line, O’Leary Line, PAO and PAT, and this underground network was financed by MI9 in London to facilitate escape and evasion of allied soldiers and airmen and is credited for assisting over 5,000 military personnel, mainly consisting of downed aircrews, to escape occupied Belgium and the Netherland and it is thought PAT rescued over 600 allied soldiers and airmen from France.

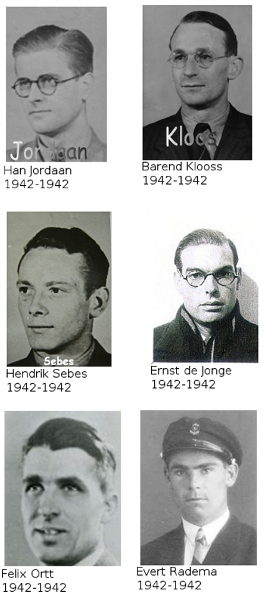

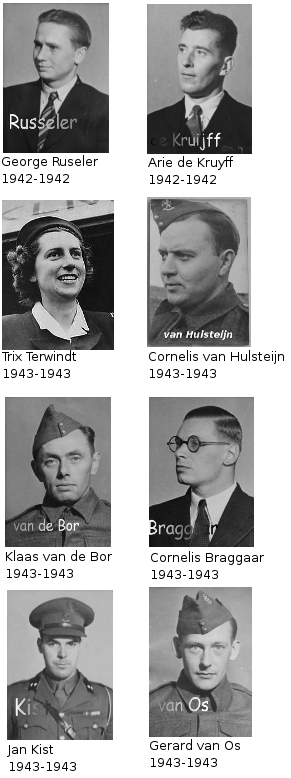

Although PAT was the largest escape line it worked jointly with MI9, DF Section SOE, the Comet Line, Shelburne Escape Line, Overcloud and several others which were established and run by French citizens after Operation Dynamo which was the emergency evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940. It has also been estimated around 12,000 people, nearly all civilians and around half of which were women worked on the escape line and a conservative estimate of the number of those captured and subsequently executed is around 500 to 575.

All these escape lines were busy throughout the war and according to author Douglas Reanne one former member said: “It was raining aviators at the height of WW2… On 14 October 1943, 82 bombers with 800 crew members of the US Eighth Air Force were shot down or crashed landed in occupied Europe. Most were killed or captured but some were rescued by the escape lines and made it safely back to England”.

There are also many accounts of RAF aircrews, which at the time was very cosmopolitan, being rescued by civilians who were aware if they were caught by the Germans they would be executed, and their families were also in mortal danger from being used as deterrents.

The Abwehr (German Military Intelligence), Gestapo and Milice were always competing for the recruitment of double agents and collaborators from the small number of morally bankrupt members of society who were willing to sell people to the Germans and were not concerned those they informed on were likely to be executed or deported to concentration camps.

This was not unique to France, in most countries under occupation could be found the morally disengaged who were willing to sell members of their communities to the highest bidder and this was often the Gestapo whose reputation for brutality was well known throughout occupied Europe.

An important part of the German and Milice counter-resistance operations was the infiltration of escape lines and blocking known routes to neutral Spain and Switzerland.

The Germans were aware the escape network consisted of a large number of civilians scattered throughout France with each member being responsible for their own section of the line (route) who delivered escapers further along the escape line where other members took over and this process continued until they reached neutral Spain; occasionally small groups of escapers were taken to an isolated prearranged location in France to wait for an emergency extraction by air or sea.

Senior Abwehr and Gestapo officers also discovered the structure of the escape network presented a number of security issues they could exploit. It’s vast size, for instance, occasionally made communications and intelligence sharing difficult and due to the network being responsible for transporting people they did not know and whose identities could be difficult to verify, German agents attempted to infiltrate networks by claiming they were airmen in need of help after being shot down or crash landing in France or Belgium and some were shot after their cover stories failed to pass scrutiny.

There is also an unsubstantiated account of the body of a German agent being placed in a packing case and posted to the Gestapo with a note saying, ‘complements of British Intelligence’.

Apart from the security issues associated with assisting ‘strangers’ whose identities could be difficult to verify the Germans were aware a double agent or a well-placed informer could cause considerable damage to the entire network and Harold Cole began using his position in the PAT line to make a lucrative income by selling men and women who trusted him to the Germans.

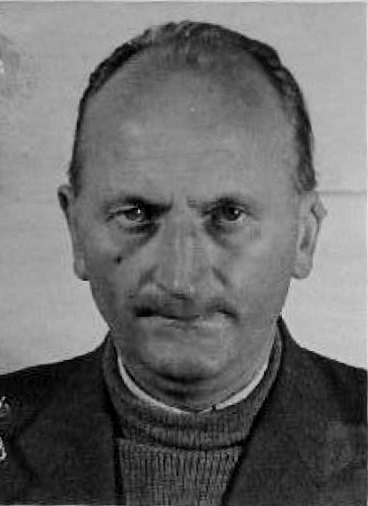

British police photograph of Harold Cole dated 13 February 1939. Five months before the BEF was sent to France.

Harold Cole was born in the east end of London on 24 January 1906 and after leaving school at the age of 14 he quickly became known to the police as a petty criminal, embezzler and con man and was sent to prison several times. During his criminal career he used several identities, during one scam he convinced people he was a former British Army officer who had served in Hong Kong and for another he claimed to be Wing Commander Wain of the Royal Air Force.

In 1939 he enlisted into the Royal Engineers and shortly after arriving in France as part of the British Expeditionary Force Cole was arrested after it was discovered he had stolen all the money from the officers and Sergeants mess before leaving England. During the confusion of Operation Dynamo, the emergency evacuation of Dunkirk, his guards were naturally more concerned in surviving the German onslaught than guarding a petty thief and Cole soon found an opportunity to escape, but after being stranded in occupied France instead of attempting to escape to England Cole felt confident he could use the occupation to his advantage and began developing a new scam.

According to Brendon Murphy who wrote ‘Turncoat’, Cole convinced a wealthy businessman named François Duprez he was Captain Delobel of British Intelligence and then persuaded him to finance an underground organisation to rescue British, French and Belgium soldiers and help them reach England. Escape lines required a string of expensive safehouses, helpers had to be paid and transport needed to be obtained and these along with other expenses finance by Duprez were considerable. Though Cole is known to have rescued a number of servicemen and helped them reach England he is also known to have kept most of the money he obtained from Duprez.

Eventually the mysterious Captain Delobel came to the attention of MI9 in London and they asked MI5 to conduct background checks. After discovering his real name and informing MI9 of Cole’s string of convictions which included burglary, fraud, theft and various swindles MI9 decided to disregard his long criminal background because he was helping British and allied military personnel to escape and there was no indication this was simply a continuation of his criminal career rather than patriotism.

After Cole was arrested by the Abwehr he willingly provided names and addresses of people in his network and was later accused of hiding in the back of a car whilst pointing out members in the street whose names he did not know. After a large number of arrests Cole agreed to work for the Abwehr but was offered more money by the Gestapo and as James Langley said he betrayed his country (and his friends) to the highest bidder and began working for the Gestapo.

Cole was arrested several times by the Germans but according to witnesses he was never roughly treated and was quickly released, and because his arrest sometimes coincided with the arrest of those he identified to the Gestapo, led to speculation these were orchestrated in an attempt to prevent raising suspicion among members of his network. Apart from Harold Cole being responsible for mass arrests in Lillie which resulted in that section of the line collapsing his close working relationship with Kurt Lischka, the Gestapo chief in Paris who after the Normandy landings helped Cole escape is testament to his importance as a double agent and his influence within the Gestapo.

Suzanne Warenghem

According to several writers Suzanne Warenghem was 19-years-old when she started working on the PAT line with Harold Cole and if correct she was one of the youngest SOE agents in France.

Warenghem has been described as intelligent, resourceful and brave but naive when it came to relationships and Cole was highly regarded for his politeness, charm, friendliness, his kindly disposition and concern for others which created a false sense of security. Those who trusted Cole, including Suzanne Warenghem who he married in Paris on 10 April 1942, were shocked after discovering he was working for the Gestapo and was aware members of the resistance he was informing on were being executed or sent to concentration camps.

After being identified as a Gestapo agent Cole is thought to have made his way to Paris to continue his work with the Gestapo and It is known he was at their headquarters in Paris when the allies landed in Normandy.

Suzanne Warenghem who was now pregnant and feared her husband, travelled to Marseille to join an escape line where some writers say her child was still born, and sometime in March 1943 she was arrested and sent to Castres prison where she met SOE agent Blanche Charlet.

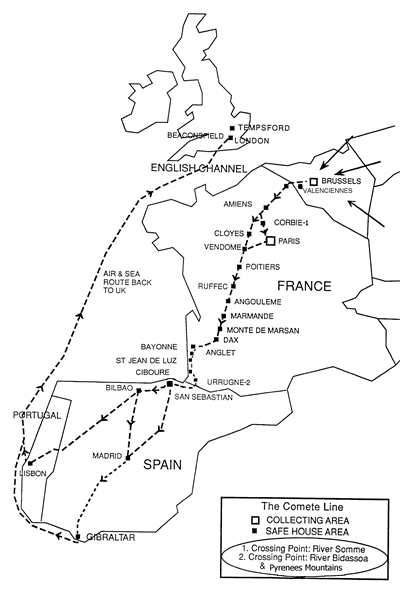

On 16 September 1943 Warenghem and Charlet escaped from prison and made for open countryside and because they had no money and were unable to contact London they decided to approach the first farmhouse they came to and ask for help whilst hoping they were patriots and to their great relief they were in luck. After explaining they worked for the resistance and had just escaped from prison they were told to climb onto the back of an open horse drawn cart, the Farmer and his family then hid them under straw before taking them to a Benedictine monastery where the monks fed and sheltered them for two months. After the search for them had been called off and it was considered safe to move through the countryside the monks delivered Warenghem and Charlet to members of the resistance who were known to be operating in the area.

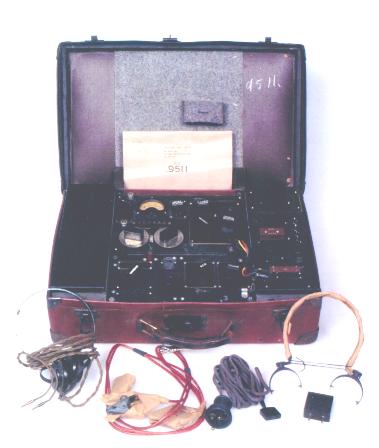

After contacting SOE in London via a wireless link they were involved in a very long and dangerous trek across France which required putting into practice all the escape and evasion skills they had been taught whilst knowing they were on the wanted list and their prison photographs were being circulated.

Suzanne Warenghem and Blanche Charlet were told to make for a rendezvous point where they would meet a guide who would take them across the Pyrenees into neutral Spain but by the time they arrived the weather had deteriorated, and the snow was too deep to cross the mountains. They were then told to make their way to Paris and await orders from London and several days later they received instructions to meet a contact in Lyon but by the time they arrived this contact had been arrested. They then received orders to go to the Jura Mountains were arrangements were being made for them to cross the border into Switzerland but shortly after making the long and difficult trip they were informed the escape line contact had been arrested several days previous. They were then given the location of a rendezvous point in Brittany around 919.8 km (over 571 miles) away where an extraction by sea had been arranged. By the time they reached Brittany and were being taken by rowing boat at night to a felucca waiting a safe distance from the shore they were suffering from extreme exhaustion and had not eaten for several days. After arriving in Gibraltar, the British Consulate arranged food, clothing and accommodation where they stayed for two weeks in order to recover from their ordeal and then boarded a ship which was part of a convoy with Royal Navy escorts bound for England.

After the war there was sufficient evidence to convict Harold Cole for treason and on 8 January 1946 he was shot dead by French police whilst attempting to evade capture.

Received from reader: “Suzanne Warenghem was my mother in law and her son Patrick lived for three months before dying of malnutrition because the nanny looking after him spent the money given to her for his care, according to Suzanne.”