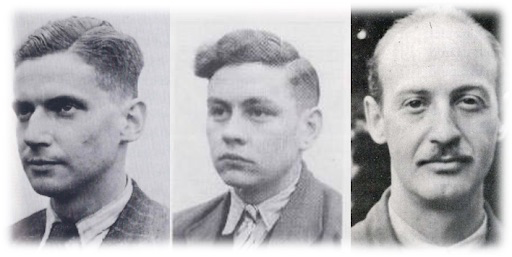

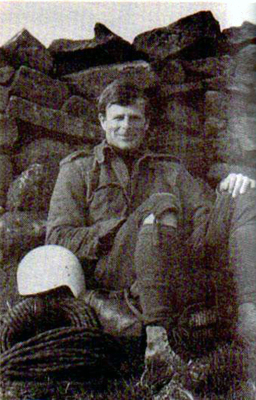

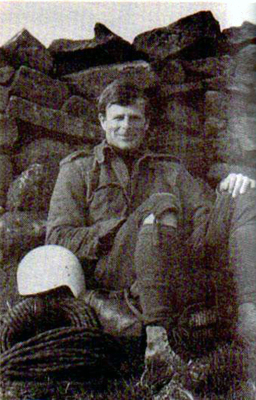

Talaiasai Labalaba (known as Laba) who some soldiers said should have been awarded the VC.

Memorial to Laba of B Squadron 22 SAS who was KIA during the battle.

Laba was born in Nawaka, Fiji on 13 July 1942 and was a sergeant serving with the Royal Irish Rangwers before joining the Special Air Service Regiment (SAS) during which he saw active service in Aden and Oman.

During the 1970s Communist guerrillas were attacking the pro-western Sultan of Oman and elements from the SAS were deployed to support the Sultan’s army.

The Fort at Mirbat

In July 1972 four-hundred heavily armed Communist guerrillas attacked the coastal town of Mirbat which was occupied by a small number of Arab soldiers and nine members of the SAS under the command of 23-year-old Captain Mike Kealy and due to being greatly outnumbered the Communists were certain of a quick victory.

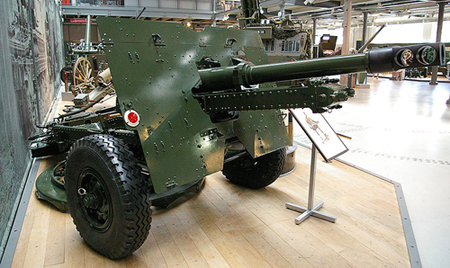

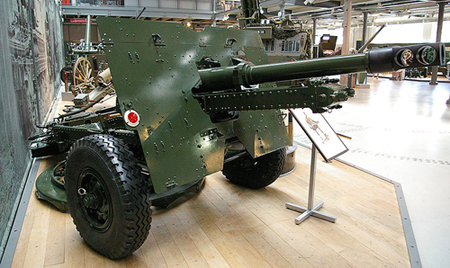

The SAS soldiers were only armed with their personal weapons, one mortar, a Browning machine gun and a Second World War 25-pounder gun.

After the Duke and Duchess of Sussex unveiled a memorial to British-Fijian SAS soldier the story of how Lab held off 250 Communist guerrillas as they attempted to overrun their position was reported by a small number of newspapers who used the words of two SAS soldiers who fought during the battle: Trooper Sekonaia Takavesi, a Britsh-Fijian known as ‘Sek’ and Corporal Peter Warne known as ‘Snapper’.

Snapper:

“A mortar salvo blew away part of the perimeter wire and a round exploded on the edge of the town. Shrapnel flew over our heads. Then I turned to see Mike Kealy clambering over a wall. He was telling me to go down to the radio and contact base… As I returned to my position and eased off the safety catch of my Browning, a massive explosion took a great chunk out of the tower.

In the flash I could see Laba, a Fijian SAS soldier, kneeling behind the shield of a 20-pounder. An hour-and-a-half or two hours later, I saw the first assault troops of about 50 advancing towards us… The battle was on. As the adrenaline kicked in the emotional shutters came down and all feelings of humanity were locked out. It’s a kind of exhilarating insanity, its kill or be killed. So we set about taking them out. The group in front were hit, the line faltered then wave upon wave of them were advancing, grabbing at the barbed perimeter wire with bare hands while Laba was blasting them into oblivion.”

20-pounder used by Laba

Sek:

“When Laba and I were firing we were under heavy attack. They were almost on top of us, shooting from all directions. We were firing at point blank range, we had no time to aim… We were pretty short of ammunition and the battle was getting fiercer. They were still advancing, and we were almost surrounded. Then Laba told me there was a 66 mm mortar {? might be 66mm LAW) inside the gate.

We were joking in Fijian and I said, ‘Laba, keep your head down’ as he crawled away towards the mortar. I was covering him then I heard a crack, I turned, all I could see was blood. A bullet had hit Laba’s neck and blood was spouting out. He died within seconds.

I had to think how to survive. I could hear the radio going, but it was too far away to call for help. Then I saw Captain Kealy and another soldier Tommy Tobin coming towards me. Tommy was the first to reach the command post and as he climbed over the wall he got shot in the jaw. I heard a machine gun fire and all I could see was his face totally torn apart. He fell and Mike Kealy dragged him to a safe area.

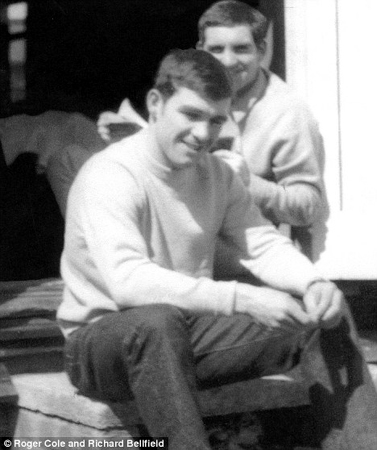

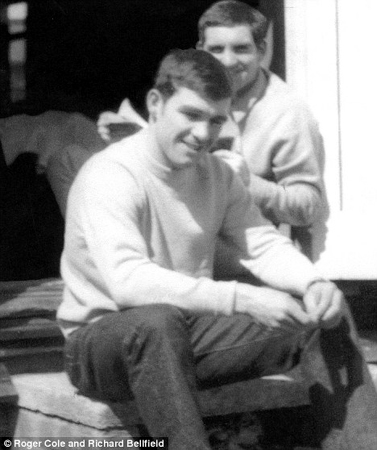

Tommy Tobin (from the book credited at the end of this article)

Then Mike got himself into an ammunition pit and started throwing loaded magazines to me.

Captain Mike Kealy (see book credit)

We could see two or three people {rebels} on the corner of the fort throwing grenades from only about four or five metres away. We managed to kill a few. All I could hear was Mike on the radio trying to get support.

As the battle raged two Strikemaster jets roared over.”

Snapper:

“The rebels turned their attention to the jets as the first strafing runs were made. They came back with bullets, rockets and a 500 kg bomb into the wadi {oasis} to the east of the fort. One jet was hit in the tail section and limped away. The other made one final run but our jubilation was short lived because the enemy had regrouped and were counter-attacking.

An SAS soldier we called ‘Fuzz’ couldn’t get the right angle with the mortar, so he lifted the barrel to his chest, hugged it like a dancing partner and slid a bomb down. Then he sent bomb after bomb right where Mike wanted them.

Two Strikemasters arrived on strafing runs and then helicopters ferried out the troops. The final toll was two SAS soldiers killed, six Arab soldiers and an Omani gunner dead and one Arab wounded. The guerrillas left behind 30 bodies and 10 wounded, although it was later indicated that half the force was killed or wounded.

Sek:

“The enemy were totally destroyed, but it was very sad to see Laba and Tobin die. I think all the people involved should have been given medals…”

Snapper:

“Laba was a bear of a man. When he was fully tooled up he was the original Rambo. They wanted to give him a VC but because the war was secret in 1972 they said it would be headlines in every newspaper in the UK.”

(Source Fiji Times 26 October 2018)

The Battle of Mirbat marked the end of the Communist rebellion and by the time the war ended in 1976 the SAS lost 12 men.

Further reading: ‘SAS Operation Storm: Nine Men Against Four Hundred’ by Roger Cole and Richard Belfield (Hodder & Stoughton)